Pigs are not native to the Americas, they originated in southeast Asia and from there expanded their range through Eurasia and North Africa1. Humans are responsible for introducing pigs everywhere else. In what is now the United States, pigs were first introduced by Polynesian settlers on the Hawaiian Islands 800 - 1000 years ago. Domesticated pigs arrived on the mainland in the 16th century, brought by European explorers and settlers2. Landing on the gulf coast of present-day Florida in 1539, Fernando de Soto is credited with bringing the first cargo of pigs. These were not the large, cumbersome pigs we are familiar with today, but a longer-legged, more athletic breed. As De Soto’s expedition proceeded through what is now the American South, pigs inevitably escaped captivity to become the ancestors of the first feral swine2. Escapees from other European colonies subsequently contributed to early feral swine populations.

In the late 19th century, sport hunting operations began to import Eurasian or Russian wild boar to provide a new game species for wealthy hunters2. Although wild boar were introduced to fenced reserves, many broke out and over the years have interbred with existing feral swine. These days, feral swine are a combination of escaped domestic pigs, wild boars, and hybrids of the two. Known as feral pigs, wild hogs, razorbacks, old world swine, wild boar, piney ridge rooters… today's feral swine go by many names but they are all the same species as domesticated pigs found on farms: Sus scrofa.

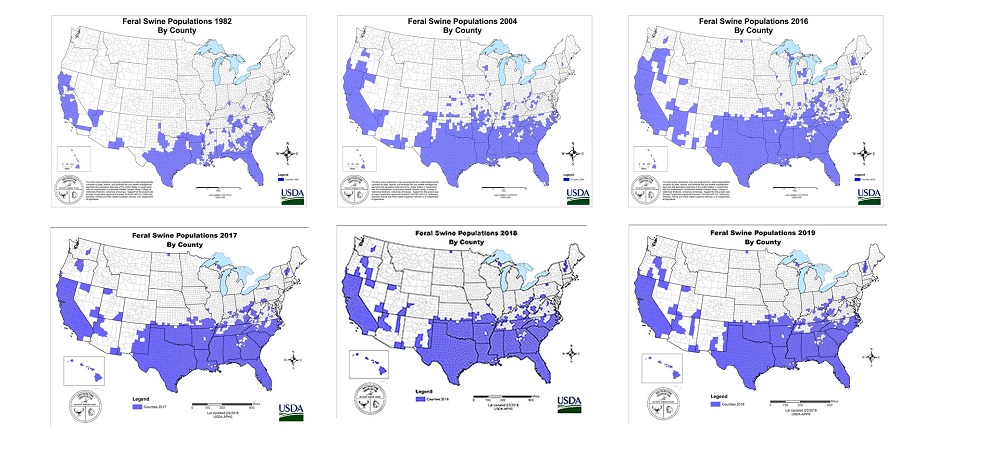

Over the last 40 years or so, populations of feral swine have been growing and expanding. This collection of maps from USDA APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) shows feral swine populations by county. At least 35 states are now reporting feral swine and their population is estimated at over 6 million and is rapidly expanding3.

Take a look at this map published in 19594. The expansion of the known distribution of feral swine in the southeast in the 1950s compared to half a century later is jaw-dropping. There has also been a more recent growth in populations in the central part of the country, which is likely the result of illegal trapping, translocation, and release by feral hog hunting enthusiasts2. Although populations are generally found in southern half of the United States, there is now a growing threat of invasion from the north. Escaped wild boar in Canada are heading south and are close to entering Montana.

The success of pigs in the wild is due to several factors. They mature early and can produce an abundance of offspring. They are generalists, meaning they can thrive in a wide variety of environments and can eat a variety of foods.5 They are also a highly adaptive and intelligent species that learns quickly to evade capture. “A wild hog is very possibly the most dangerous animal in the wild, and he knows no enemies and he knows no fear” Hank Berdine, Mississippi Levee Board.

They are a destructive, invasive species that causes extensive damage to natural ecosystems, croplands, pastures, livestock operations. The USDA estimates that feral swine are responsible for $2.5 billion in damage to U.S. agriculture annually. Through the scale of the destruction that they inflict on soil, grasslands, trees, wild plants, crops and waterways and the threat they pose to rural livelihoods, livestock and wildlife, feral swine are one of the most devastating invasive species in the U.S. today.

Feral swine damage pastures, by rooting, killing desirable pasture species, and facilitating the growth of weeds. They damage crops by eating them, and by rooting, trampling, and wallowing. They will eat almost anything, but most often target sugar cane, corn, grain sorghum, soy beans, wheat, oats, peanuts, and rice. Tasty vegetable and fruit crops can be particularly vulnerable to a hungry pig. This video shows some of the damage to field crops in Mississippi, both for large scale farmers and subsistence farmers.

Feral swine damage orchards and vineyards in several ways. Apart from eating the fruit and nuts, they will destroy young trees and vines by using them to scratch. Male pigs will scrape bark from trees with their tusks to mark their territory. Feral swine will tear up or break any kind of orchard or vineyard infrastructure such as irrigation lines, nets, trellises, etc. In Hawai’i, they will gnaw through the pseudostem of a banana plant to access the water contained within, and to get to the banana fruit (below). Their rooting also destroys the orchard floors – an issue that is particularly problematic for pecan farmers who need a smooth surface for harvesting. This video shows the challenges that pecan farmers face in dealing with invasive feral swine.

Feral swine can carry and / or transmit 30 diseases and 37 parasites to livestock, pets, and wildlife including pseudorabies, swine ‘flu, toxoplasmosis, tularemia, trichinellosis and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. These pathogens and others can be passed to livestock via contaminated feed, mineral supplements, or water. Feral swine also carry zoonotic pathogens that “pose a significant threat to public health,” such as brucellosis, bovine tuberculosis, leptospirosis, salmonella, E. coli, and hepatitis E.6 Aside from their disease risk, feral swine will attack and kill young livestock such as calves or lambs, and even vulnerable adult animals during birthing.

Feral swine are ecosystem engineers, impacting natural ecosystems at multiple trophic levels across local to landscape scales7. The signs of pigs’ rooting behavior are unmistakable. They break through the surface layer of vegetation and will excavate soil and litter to depths between 5 – 15 cm. Disturbed areas may cover as much as 2 acres, and are typified by patches of damage8. In forests, rooting and foraging by feral swine adversely affects tree species diversity and depletes food sources for native species such as deer and turkey. Through foraging and rooting, feral swine also detrimentally impact soil properties such as organic matter, and soil aggregate stability, and their feces alter the nutrient balance within soil.9

What is USDA-APHIS doing about feral swine?

Without appropriate and coordinated management and removal of feral swine, the U.S. could witness a “feral swine bomb.” In response to the multiple threats posed by this invasive species, Wildlife Services within the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is coordinating the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program (NFSP - initiated in 2014). The NFSP aims to manage the damage caused by invasive feral swine with the primary goal of protecting agricultural and natural resources, property, animal health, and human health and safety by reducing feral swine damage in the United States and its territories. Through a coordinated national effort, they work closely with partners at the Federal, State, and local levels to address the extensive damage caused by feral swine populations.

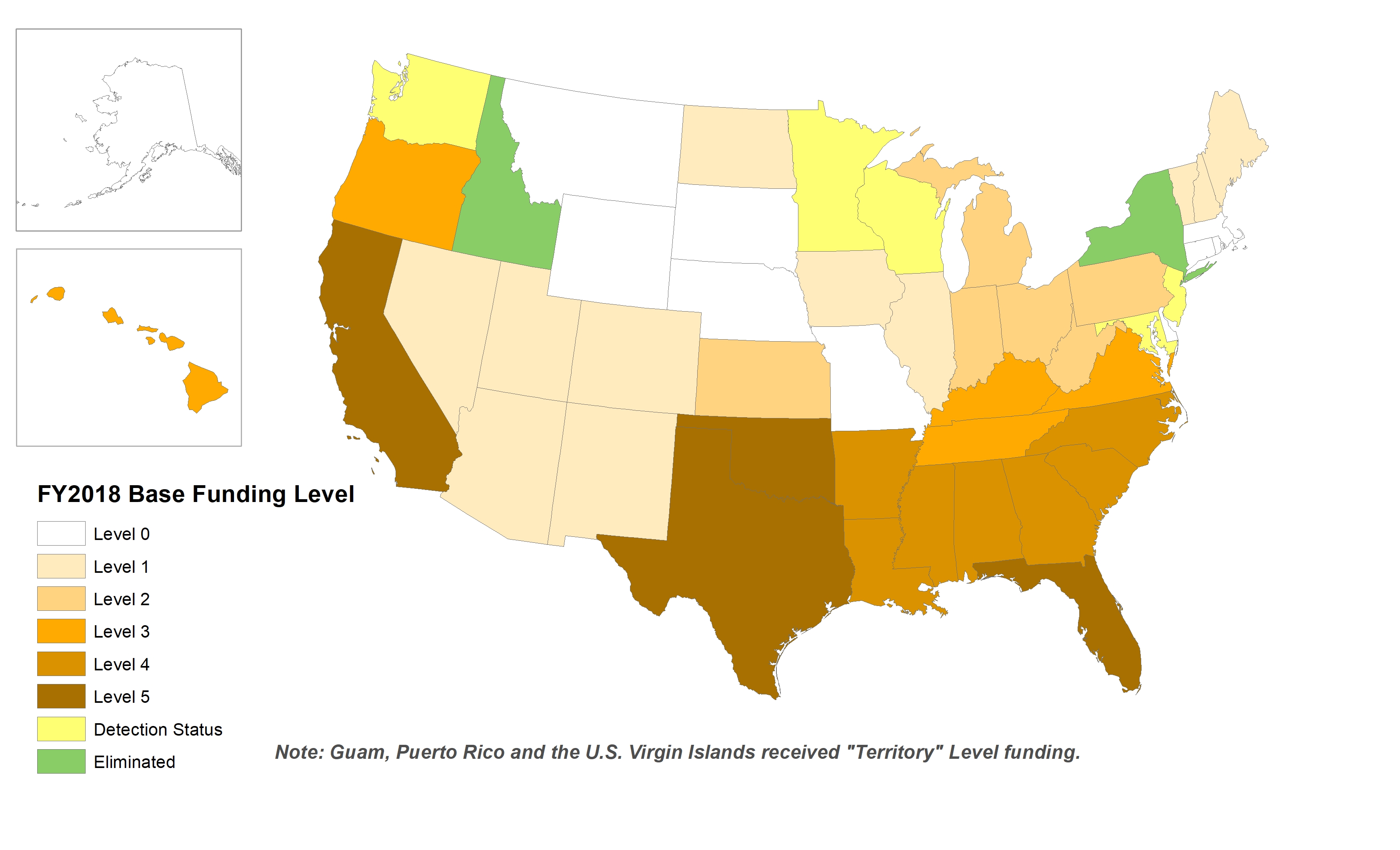

Laws governing feral swine vary considerably among states, thus APHIS’ strategy is to provide resources and expertise at a national level, while allowing flexibility to manage operational activities from a local or state perspective. Each state is classified by level depending on the number of feral swine estimated to be there. This is a tiered system with level 5 indicating states with the largest feral swine populations and who received the highest baseline funds. The map below shows the funding levels in 2018 .

The NFSP and partners have been instrumental in reducing the number of feral swine on the landscape and this has helped limit the damage these animals can inflict on natural and agricultural resources. Between 2014 and 2018, Idaho and New York managed to eliminate feral swine entirely, and 10 more states transitioned to a lower level of funding, indicating that their feral swine populations were falling.

To read more about the first five years of the NFSP, and for more detail on the objectives and accomplishments in each state, please refer to the report APHIS National Feral Swine Damage Management Program Five Year Report FY14-FY18

Citations

- Wehr, N. H. (2020). Historical range expansion and biological changes of Sus scrofa corresponding to domestication and feralization. Mammal Research, 1-12.

- History of Feral Hogs in the United States eXtension

- History of Feral Swine in the Americas USDA-APHIS

- Hanson, R. P., & Karstad, L. (1959). Feral swine in the southeastern United States. The Journal of wildlife management, 23(1), 64-74.

- Aschim, R.A., & Brook, R.K. (2019). Evaluating Cost-Effective Methods for Rapid and Repeatable National Scale Detection and Mapping of Invasive Species Spread. Sci Rep 9, 7254 (2019).

- Brown, V. R., Bowen, R. A., & Bosco‐Lauth, A. M. (2018). Zoonotic pathogens from feral swine that pose a significant threat to public health. Transboundary and emerging diseases, 65(3), 649-659.

- Wehr, N. H., Hess, S. C., & Litton, C. M. (2018). Biology and impacts of Pacific islands invasive species. 14. Sus scrofa, the Feral Pig (Artiodactyla: Suidae) 1. Pacific Science, 72(2), 177-198.

- Kotanen, P. M. (1995). Responses of vegetation to a changing regime of disturbance: effects of feral pigs in a Californian coastal prairie. Ecography, 18(2), 190-199.

- Long, M. S., Litton, C. M., Giardina, C. P., Deenik, J., Cole, R. J., & Sparks, J. P. (2017). Impact of nonnative feral pig removal on soil structure and nutrient availability in Hawaiian tropical montane wet forests. Biological Invasions, 19(3), 749-763.

Other recent publications and resources on feral swine

APHIS National Feral Swine Damage Management Program Five Year Report FY14-FY18

Feral Swine: An Overview of a Growing Problem

Feral Swine: Damages, Disease Threats, and Other Risks

Identifying and Reporting Feral Swine

Feral Swine: Impacts to Native Wildlife

Feral Swine: Impacts on Threatened and Endangered Species

Link to APHIS Publications on Feral Swine

Videos

Feral Swine in America USDA-APHIS 2020. Youtube watchlist on feral swine - recommended viewing!

Feral Swine: Manage the Damage (2019) USDA-APHIS

Virtual Wild Pig Conference 2020 National Wild Pig Task Force