Every decade a suite of standardized climate metrics known as "climate normals" are calculated, providing averages of temperature and precipitation data over the previous 30-year period. When "average climate" is referenced in news articles, or when the local weather notes that the temperature on a given day was warmer or cooler than "normal," these 30-year "climate normals" are often the baseline for those comparisons. However, there are numerous additional ways to measure climate conditions that are more directly applicable to agricultural producers besides average temperature and precipitation. For example, producers use growing degree days to make decisions around annual crop varieties, track crop and pest development, and plan for pest management actions. For perennial fruit and nut growers, chill accumulation is an important agroclimate metric because it governs when (or if) trees will wake up from their winter slumber. And for all types of crops all across the state, farmers must take into consideration environmental conditions like growing season length, heat and frost exposure, and crop water requirements.

To provide information on contemporary climate conditions for California agriculture, scientists at the USDA California Climate Hub, UC Davis, UC Merced, and UC ANR identified a suite of agroclimate metrics and calculated how they have changed over the two most recent climate normal periods (1981-2010 and 1991-2020), and the trends in these metrics over the 40-year 1981-2020 period.

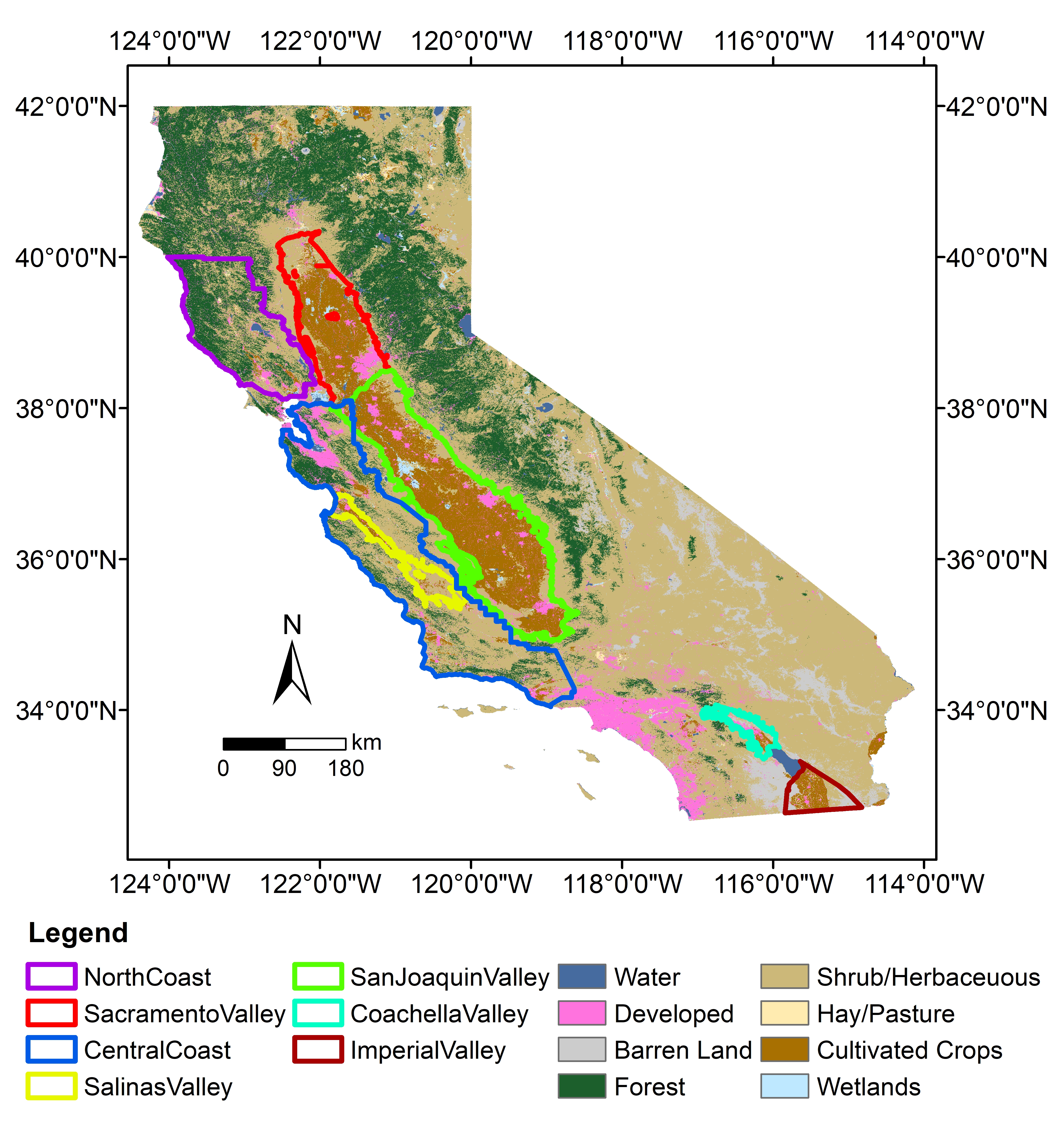

In California, a favorable climate and extensive water infrastructure have allowed for the cultivation of a wide variety of crops. The state produces forage, fiber, livestock, aquaculture, grains, and dairy, but is perhaps best known for its production of high-value specialty crops, including more than ⅓ of U.S.-grown vegetables and more than ⅔ of U.S.-grown fruits and nuts, by volume. Specialty crops are grown across the state, covering more than 1.8 million acres. The majority of acreage is found within five agricultural valleys (the Sacramento, San Joaquin, Salinas, Coachella, and Imperial Valleys), and in the North Coast and Central Coast regions which are principally known for their winegrape production. Researchers used these seven regions to provide more local context for their analysis and focus on the agroclimate metrics that might be of particular importance for the crops grown in a given area. Click the image to the right to enlarge it and see the outlines of these agricultural regions.

In California, a favorable climate and extensive water infrastructure have allowed for the cultivation of a wide variety of crops. The state produces forage, fiber, livestock, aquaculture, grains, and dairy, but is perhaps best known for its production of high-value specialty crops, including more than ⅓ of U.S.-grown vegetables and more than ⅔ of U.S.-grown fruits and nuts, by volume. Specialty crops are grown across the state, covering more than 1.8 million acres. The majority of acreage is found within five agricultural valleys (the Sacramento, San Joaquin, Salinas, Coachella, and Imperial Valleys), and in the North Coast and Central Coast regions which are principally known for their winegrape production. Researchers used these seven regions to provide more local context for their analysis and focus on the agroclimate metrics that might be of particular importance for the crops grown in a given area. Click the image to the right to enlarge it and see the outlines of these agricultural regions.

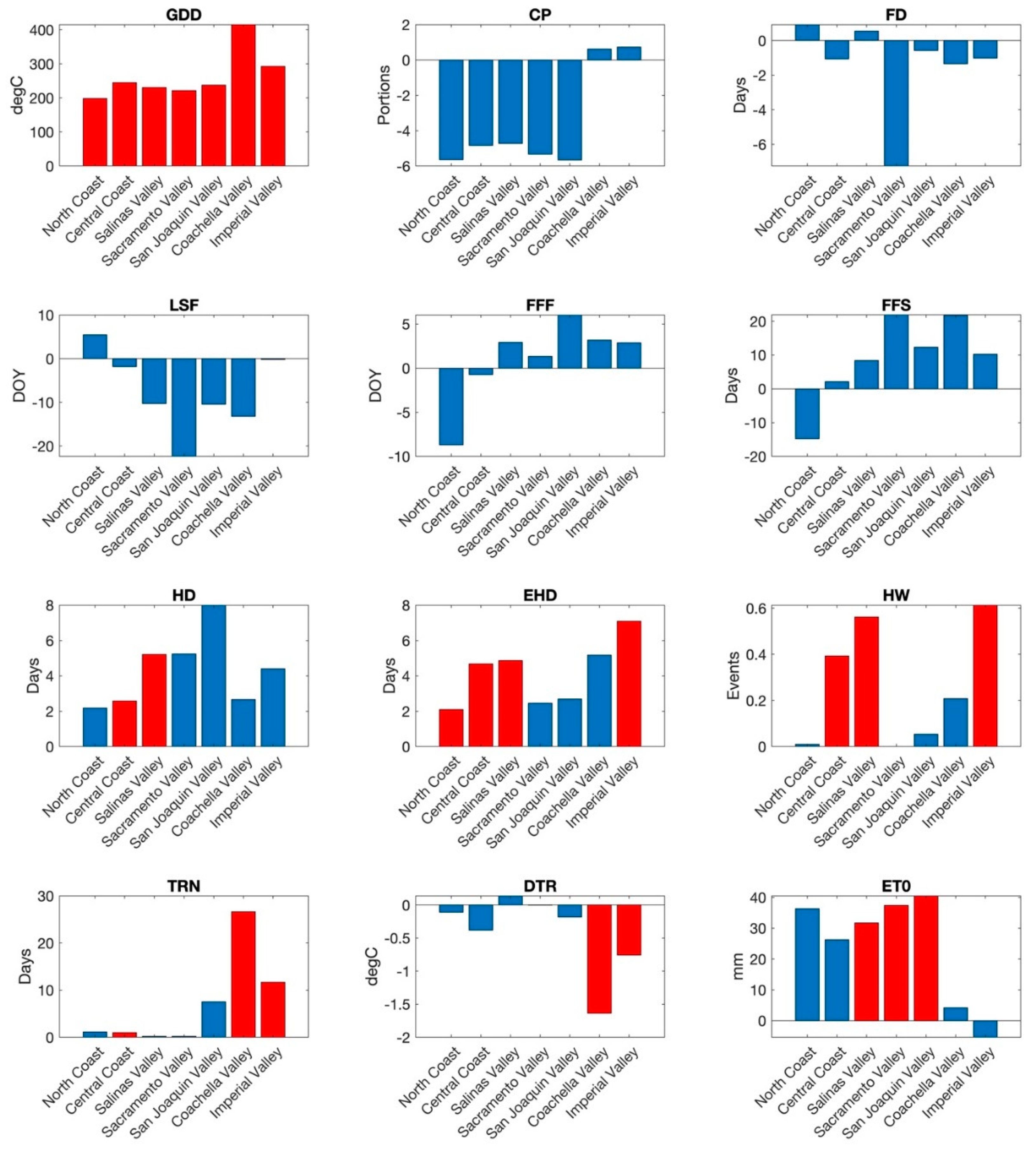

Unsurprisingly, the research shows that some agroclimate metrics are changing more than others, and the degree of change depends on location. But, regardless of the agroclimate metric or the location, all trends point toward a warming world. Growing degree days and evapotranspiration increased and chill accumulation decreased over the 40-year period, the growing season is longer and there are more heatwaves now than 40 years ago on average. The image below shows the 40-year trends in the agroclimate metrics at the regional level.

Click the figure on the left to see the trends in 12 agroclimate metrics over the 40-year (1981–2020) period averaged over crop locations in each agricultural region. Trends are per year. Metrics in red are statistically significant. Metrics are shown as: row 1: growing degree days (GDD), chill portions (CP), frost days (FD); row 2: last spring freeze (LSF), first fall freeze (FFF), frost-free season (FFS); row 3: heat days (HD), extreme heat days (EHD), heatwaves (HW); row 4: tropical nights (TRN), diurnal temperature range (DTR), summer reference evapotranspiration (ETo).

Click the figure on the left to see the trends in 12 agroclimate metrics over the 40-year (1981–2020) period averaged over crop locations in each agricultural region. Trends are per year. Metrics in red are statistically significant. Metrics are shown as: row 1: growing degree days (GDD), chill portions (CP), frost days (FD); row 2: last spring freeze (LSF), first fall freeze (FFF), frost-free season (FFS); row 3: heat days (HD), extreme heat days (EHD), heatwaves (HW); row 4: tropical nights (TRN), diurnal temperature range (DTR), summer reference evapotranspiration (ETo).

The trends and changes in agriculturally-important climate metrics that have been observed in California provide important context for expected future conditions given climate change. In fact, the trends in more growing degree days, less chill accumulation, more heatwaves, less frost, and longer growing seasons that we have seen over past decades are expected to continue - and may accelerate - in the future. California's farmers are already responding to these changes through taking adaptive actions like increasing irrigation to mitigate heat, adopting new soil amendment practices to increase soil health and soil water holding capacity, adapting their planting and harvesting schedules to adjust to growing season changes, and even planting new crop varieties better suited to today's conditions. These actions and more will be needed in the future to maintain California's agricultural production.

To read the full research article, click here. This work was supported in part by USDA NIFA (Award # 2021-68012-35914).