Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

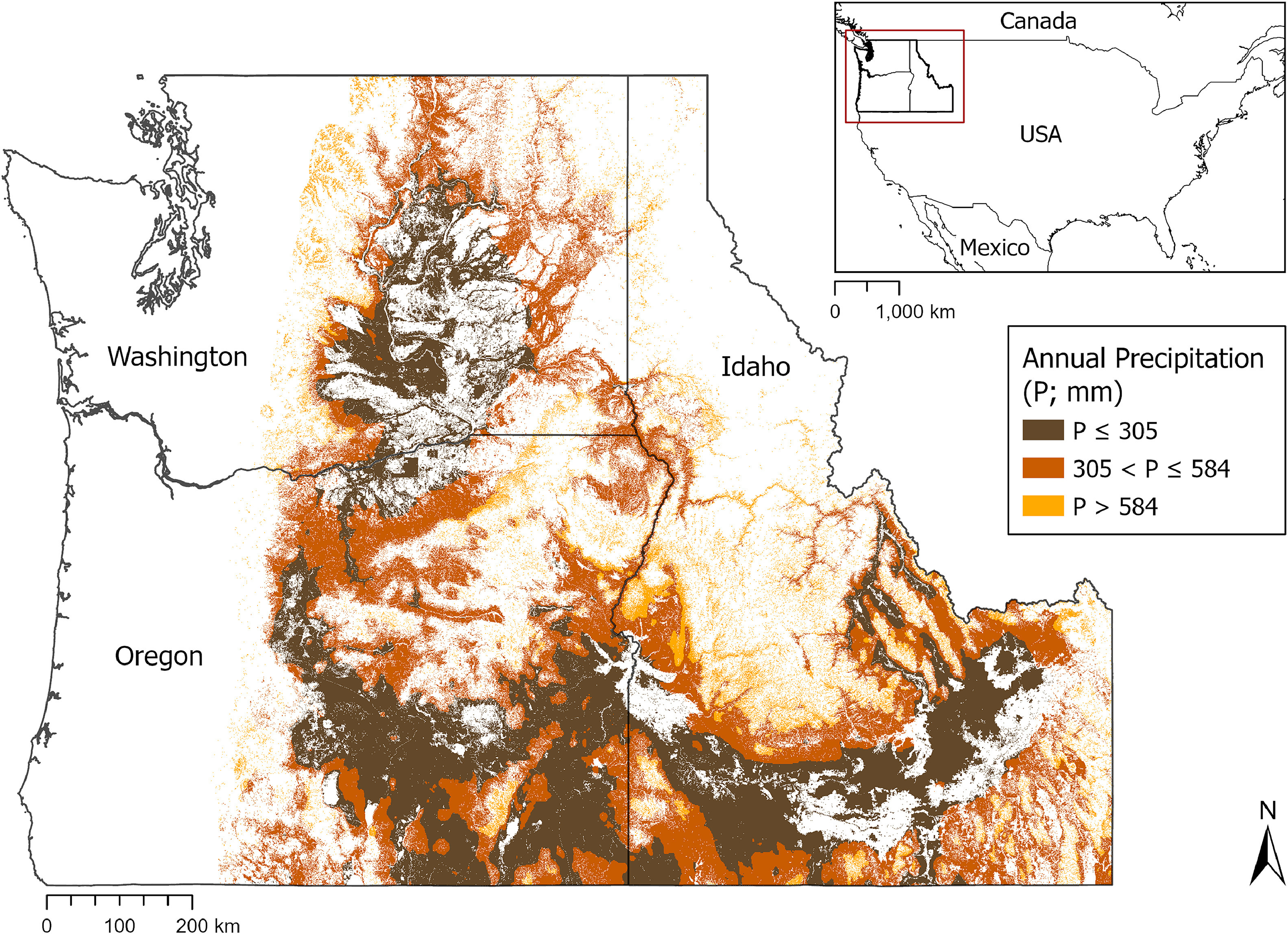

The rangelands of the inland Northwest extend from the east side of the Cascade Range in Oregon and Washington to the Snake River Plain of southern Idaho. They are primarily made up of sagebrush and bunchgrass steppe and shrublands. Wildfire is a natural disturbance in rangelands. However, climate change, invasive annual grasses, and human activities are increasing the frequency, severity, and size of wildfires. These changes threaten human safety and infrastructure, natural resources, and wildlife habitat.

How are wildfire patterns changing in Northwest rangelands?

Climate change, along with invasive annual grasses and human ignitions, have led to an increase in area burned, longer fire seasons, and more frequent and severe wildfires in inland Northwest rangelands. Since 1900, average annual temperatures in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington have increased by nearly 2° F. By 2080, temperatures are expected to rise by 4.7 to 10.0° F relative to the 1950–1999 period. Rising temperatures increase the likelihood of drought and extreme heat, both of which lead to drier soils and vegetation and more frequent fire weather. These conditions increase the risk of wildfire in the inland Northwest. As a result, more acres of rangeland than forest land have burned in the West since 2000. Mega-fires (fires that burn 100,000 acres or more) are also becoming more common, especially on the Snake River Plain and in the Northern Great Basin.

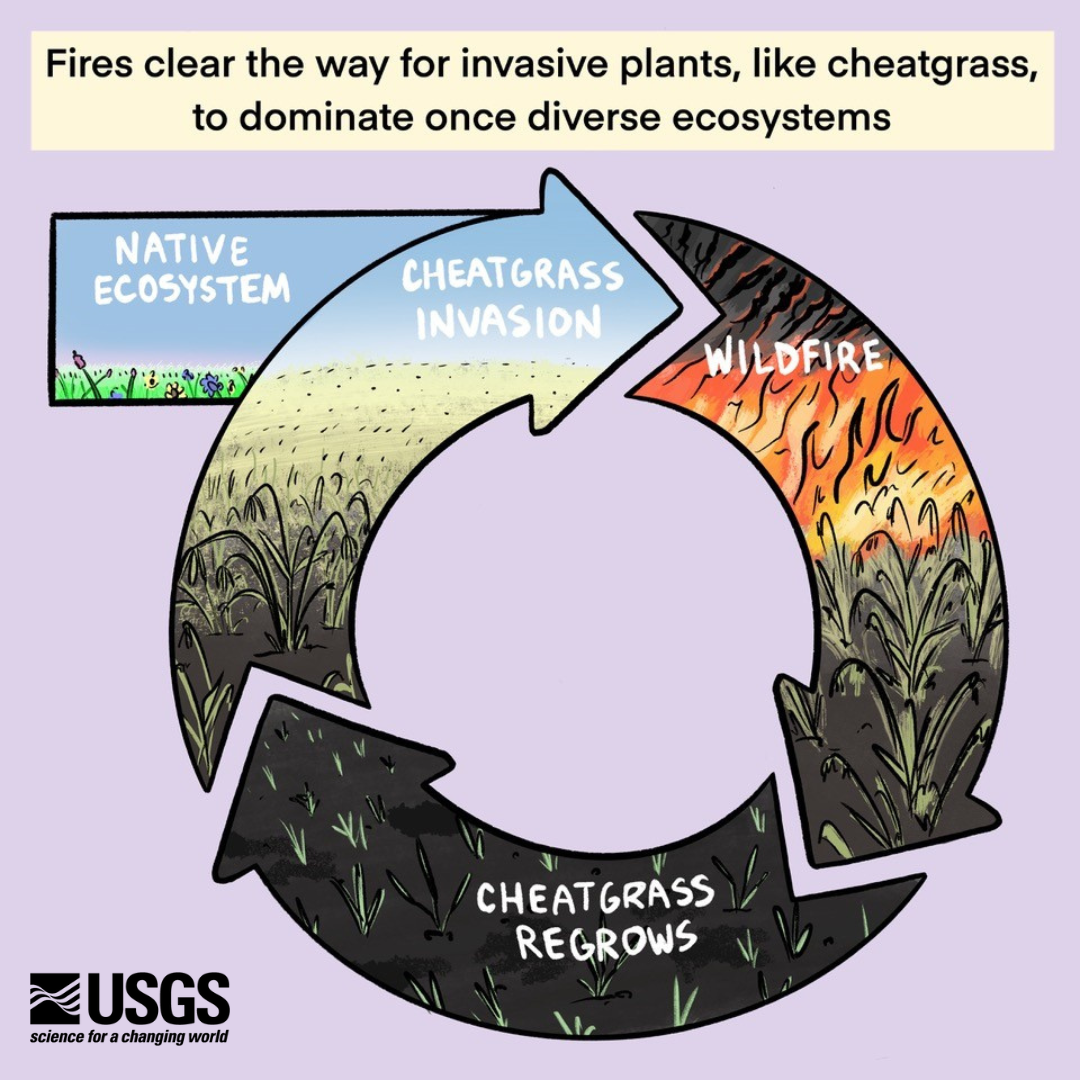

Invasive annual grasses, mainly cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), ventenata (Ventanata dubia), and medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae), are one of the most influential factors in changing rangeland wildfire patterns. These grasses grow quickly in the spring and fill the space between native plants, creating a continuous layer of fine fuel that burns easily. Invasive annual grasses also tend to dry out earlier in the year, which can lead to fires igniting earlier than average. Rangeland fire frequency has already increased because of these grasses. Areas with an abundance of cheatgrass are twice as likely to burn as those with very little, and are more likely to burn multiple times in a short period. Areas that used to burn once every 20 to 100 years can now burn every 7.5 to 15 years in sagebrush rangelands.

With rising temperatures and reduced snowpack, the growing season has lengthened, allowing invasive annual grasses to spread into new areas and higher elevations. Annual grasses now dominate one-fifth of Great Basin rangelands, an 800% increase since 1990. Their range is likely to expand as the climate continues to warm, particularly if spring precipitation increases. Human ignitions (which account for 74.5% of fires in cheatgrass-dominated areas) are also contributing to increased fire frequency, earlier fire ignitions, and an increased number of fires in areas that have recently burned. People have started several of the largest rangeland fires in U.S. history, including the Martin Fire (Nevada) that burned 435,000 acres in 2018.

How is changing wildfire affecting Northwest rangelands?

Impacts to human health and safety: Larger, more frequent wildfires threaten human safety, infrastructure, and livelihoods. For example, in 2023, the Wanes Gray Fire near Medical Lake, Washington burned through rangeland and timber, destroying 259 structures, and burning over 10,000 acres. In 2015, the Soda Fire burned nearly 280,000 acres in southwest Idaho and southeast Oregon, including 200,000 acres of greater sage-grouse habitat and portions of 41 grazing allotments. Fires of this size are becoming more common in the inland Northwest.

Wildfire smoke impacts human health. Smoke degrades air quality, and can severely affect the health of children, the elderly, pregnant individuals, and individuals with respiratory conditions. Wildfires can also reduce water quality. After a fire, runoff and erosion can increase substantially. This can lead to sedimentation and chemical changes that degrade the quality of aquatic habitat and drinking water.

Loss of sagebrush habitat and conversion to invasive annual grassland: Cheatgrass and other invasive annual grasses produce many seeds and can reestablish very quickly after a wildfire. Native plants like sagebrush and perennial bunchgrasses require more time to reestablish and produce seeds. This leads to a positive feedback loop between invasive annual grasses and wildfire: fire makes room for more cheatgrass, which encourages more fire and so on. Because frequent wildfires make sagebrush recovery nearly impossible, over time, this positive feedback loop can lead to a conversion of sagebrush landscapes to invasive annual grasslands.

Loss of wildlife habitat: Greater sage-grouse (the largest grouse in North America) depend on sagebrush for breeding habitat and forage. More frequent and severe wildfires can reduce sage-grouse habitat. Since 1984, over 22 million acres of sage-grouse habitat have burned in the Great Basin. If current fire trends continue, half of the sage-grouse population in the Great Basin could be gone by the mid-2040s. Other species that are affected by sagebrush habitat reduction include pygmy rabbits, sage thrashers, and sharp-tailed grouse. Loss of wildlife habitat can affect cultural values, and impact the experience of hunters, anglers, and recreationalists.

Impacts to livestock operations: Both wildfire and annual grasses can impact yearly livestock grazing rotations, stocking rates, and rangeland management. Though invasive annual grasses can provide forage for a short period in spring, they dry out quickly and become unpalatable to livestock. Because they outcompete native grasses that are palatable later in the season, invasive annual grasses reduce the availability of late-season forage. The increasing frequency and severity of rangeland fires can also reduce forage amounts. Following a wildfire, public grazing allotments can be closed for several years to allow restoration of burned areas. In these conditions, ranchers and rangeland managers must find alternate sources of summer forage, which can be expensive and time consuming.

Impacts to rangeland carbon sequestration potential: The combination of the invasive grass-fire cycle and the loss of woody plants like sagebrush suggest that less carbon can be stored in annual grass-dominated ecosystems than sagebrush systems. Conversion of deep-rooted perennial systems to shallow-rooted annual grasses can result in the loss of persistent below-ground carbon. Because most of the carbon stored in rangeland systems is stored in the soil, losing below-ground carbon has serious implications for rangeland carbon storage potential.

What can we do about climate change and wildfire in Northwest rangelands?

There are several adaptation strategies that can increase the resilience of rangelands and decrease wildfire severity and size. Regularly monitoring rangelands for invasive species, responding rapidly to invasion, restoring invaded or partially invaded rangelands, and managing fuels are a few effective climate adaptation strategies. In all cases, collaboration between local ranchers, land management agencies, and partners across large landscapes will increase the effectiveness of treatments. It is crucial that treatments do not introduce invasive plant species or diminish the ability of the ecosystem to resist the establishment of invasives.

Monitoring, early detection, and rapid response

For uninvaded rangelands, regular monitoring can encourage early detection of invasive annual grasses. Responding rapidly to invasion in previously uninvaded areas can deter the long-term establishment of invasives. Response can include the use of selective herbicides, reseeding with perennial grasses, and reducing litter that facilitates annual grass seed germination. Because areas with an abundance of perennial grasses are less likely to be invaded by cheatgrass, less likely to burn, and more likely to recover if a wildfire occurs in the area, early detection and rapid response to invasive annual grasses is more effective and cost-efficient than restoration of already invaded rangelands. Defending these core areas ensures that islands of resilience persist despite widespread invasion of annual grasses.

Restoring invaded rangelands

Increasing the number of perennial plants and removing invasive plant seed sources from already invaded landscapes is an effective, albeit more costly, adaptation strategy. This strategy is particularly effective in transitional areas between heavily invaded zones and uninvaded zones. Herbicide applications can target invasive annual grasses and protect native seedlings. Replanting of native grasses and shrubs can restore invaded landscapes, especially after a fire. To minimize annual grass invasion, it is important to reseed perennial bunchgrasses quickly postfire. Managers must carefully consider the costs and benefits of each management decision, as reseeding and replanting can be expensive and challenging.

Managing fuels

Though eradicating invasive annual grasses from heavily invaded areas may prove impossible, heavily invaded areas must be managed, particularly near communities and valued resources. Restoring large swaths of invaded rangelands is costly and difficult. Instead, adaptation actions in heavily invaded areas can prioritize protecting nearby communities from larger, more frequent wildfires associated with invasives. Fine fuels (e.g., grasses) can be managed to reduce fuel load and continuity. Targeted grazing of invasive annual grasses can decrease wildfire probability, spread, and severity. Because cheatgrass and other annual grasses are only palatable to livestock in the spring, changes to grazing leases and allotments may be required. Well-planned and flexible grazing strategies can help to meet a variety of rangeland and fire-management goals.

Fuel breaks are another effective adaptation action. Fuel breaks are areas where vegetation has been reduced or removed to slow the spread and decrease the intensity of wildfire. They can also make it easier and safer for firefighters to combat wildfires. There are many ways to create fuel breaks, including prescribed burns, targeted grazing, chemical treatments, and mechanical treatments (e.g., mowing, dozing). On the I-84 corridor between Boise and Mountain Home, Idaho, Bureau of Land Management fuel breaks reduced average fire size by 95% over 7 years. While fuel breaks are effective, they can also disrupt and damage critical wildlife habitat. Land managers need to use fuel breaks strategically to balance fire risk reduction with habitat damage.

A changing range

Climate change, invasive annual grasses, and human activities have contributed to an increased risk of large and frequent wildfires in Northwest rangelands. Managing rangeland wildfires is a complex, evolving issue that requires interagency coordination. However, protecting intact sagebrush habitats, reducing the spread of invasive annual grasses, and restoring native shrublands can help to manage wildfire risk and impacts in the region.

The Rangeland Analysis Platform is an online tool that visualizes and analyzes vegetation data (including annual forb and grass coverage) for the United States, including the Northwest.

Great Basin Rangeland Fire Probability Map represents the relative probability of large (> 1,000 acres) rangeland fire given an ignition in a given year. Maps are updated yearly.

FuelCast provides monthly fuel and fire forecasts during the growing season to help users stay up to date on fire danger. It is updated monthly during the growing season.

Science Framework for Conservation and Restoration of the Sagebrush Biome links the Department of Interior’s Integrated Rangeland Fire Management Strategy to long-term strategic conservation actions.

Sagebrush Biome: A Framework for Conservation Action is a Natural Resource Conservation Service publication that provides a framework for conserving sagebrush steppe and shrublands.

Climate Change Vulnerabilities and Adaptation Strategies for Land Managers on Northwest US Rangelands is a research paper written by USDA Northwest Climate Hub scientists and partners.

Expanding the Invasion Footprint: Ventenata Dubia and Relationships to Wildfire, Environment, and Plant Communities in the Blue Mountains of the Inland Northwest, USA is a U.S. Forest Service journal article that explores the emerging relationship between Ventenata dubia and wildfire in the Blue Mountains of Oregon and southeastern Washington.

Rangeland Fire Protection Associations organize and authorize rancher participation in fire suppression alongside federal agency firefighters.

Idaho’s Cheatgrass Challenge is a proactive effort, led by the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), to tackle annual invasive grasses and other restoration challenges across Idaho.

The Sage Grouse Initiative is an NRCS program that offers technical and financial assistance to help ranchers voluntarily conserve sage grouse habitat on private lands.