A century of wildfire suppression

A prescribed fire on the lowland prairies near Puget Sound. Credit: JBLM Fish and Wildlife

A prescribed fire on the lowland prairies near Puget Sound. Credit: JBLM Fish and WildlifeFrom abundant forests to sweeping grasslands to northern tundra, the landscapes of the Northwest Climate Hub region have a deep history of wildfire and cultural fire. Prior to the twentieth century, North American forests showed a natural resistance and resilience to wildfires, largely due to the regularity with which forests experienced fire. Historically, smaller fires burned at regular intervals throughout much of the Northwest, resulting in many ecosystems becoming fire adapted.

Yet a different ecological tale unfolded over the last century. Catastrophic events like the Big Burn Fires of 1910 catalyzed a nationwide policy of wildfire suppression, a tactic that severely limited the presence of wildfire on Northwest lands. Without relatively frequent wildfire, many ecosystems in the Northwest have fundamentally changed.

Many fire-dependent ecosystems, like mixed-conifer forests, have become unhealthy due to overcrowding, disease, and insect outbreaks. Species that need fire to regenerate, like white pine and aspen, are diminishing, while a century of fuels have accumulated, posing a risk of intensifying wildfires in the future.

Additionally, fire seasons have lengthened throughout the western United States since the 1970s, and droughts have intensified, increasing the abundance of dried fuels. Extreme fire weather events, defined by abundant dry fuels, low relative humidity, and strong winds, are increasingly common and present an opportunity for rapid fire growth, as witnessed in the 2021 Bootleg Fire in Oregon. With more people living and recreating in the wildland-urban interface, fires are also more likely to spark near populated areas. When fires do occur in overgrown areas with dry fuels, fire can spread quickly, threatening nearby communities, firefighters, wildlife, and habitats.

What is prescribed fire?

There are tools that land managers can use to decrease the risk of severe wildfire near communities and valued resources. Prescribed fire—planned low-intensity fire conducted by professionals—can reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires by reducing fuels. Prescribed fire seeks to mimic the small, regular-interval fires historically experienced in many Northwest ecosystems.

Prescribed fires are shorter in duration than wildfires, conducted under favorable weather, planned far in advance, and obey the air quality regulations of nearby communities.

Planning the burn:

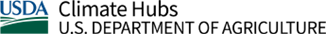

A prescription is written that addresses the size of the prescribed fire, the vegetation type, and what managers hope to accomplish with the fire. The prescription will also address weather restraints (like not burning above a certain air temperature or below a certain relative humidity), air quality regulations, and “trigger-points,” or situations in which the prescribed fire will be extinguished. Land managers also decide how firefighters will set the fire based on weather and topographical features, how smoke levels will be managed, and how many firefighting resources are needed.

Before the burn:

Firebreaks (breaks in woody vegetation) are established to contain the fire within the prescribed area. Firebreaks can consist of creeks, roads, rocky areas, or handline cut and dug by firefighters. A qualified burn boss will supervise all phases of pre-burning, burning, and post-burning. Before ignition, they will ensure all firefighters are properly prepared, all firebreaks look suitable, all hazards have been identified, and nearby communities have been notified. If weather, timing, and resources are favorable, the burn boss will conduct a small “test fire” in the downwind corner of the burn area near a firebreak to evaluate burn conditions.

During the burn:

If the test fire is favorable, the burn boss will direct firefighters to begin igniting. There are many different ignition patterns that can be used, depending on slope, terrain, fuels, and desired effects. Depending on desired effects and the stability of weather and fuels conditions, the burn boss will evaluate whether fire intensity needs to decrease, increase, or stay the same. The burn boss and firefighters will evaluate these conditions throughout the burn. When firefighters have ignited to the limits of the prescribed burn area, they will transition to post-burning methods.

After the burn:

Firefighters will patrol the perimeter of the prescribed burn, ensuring that the fire stays within the firebreak. Firefighters will “mop-up,” or extinguish fire and heat where needed. Firefighters will patrol the burn until it has stopped burning, smoking, and emitting heat (usually a few days to a few weeks).

| Immediate Evaluation | Future Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Overstory discoloration and mortality | Signs of disease or insect attacks |

| Understory fuel consumption and mortality rate | Tree and vegetation mortality |

| Litter and duff remnants on forest floor | Regeneration of plants |

| Exposure of mineral soil | Remaining duff layer/soil exposure |

| Desired impacts to target species | Invasive species |

| Unwanted impacts to non-targeted species | Plant reproductivity |

What are the benefits of prescribed fire?

Conducting prescribed burns in the right season and under optimal conditions can:

- Decrease wildfire intensity and severity

- Reduce the threat of future wildfires in the same area

- Create a buffer area for communities and firefighters

- Reduce ladder fuels and debris from logging or thinning

- Promote new growth of trees, plants, and fungi

- Minimize the spread of invasive species, insects, and disease

- Provide forage for wildlife

- Increase subsistence and recreational access

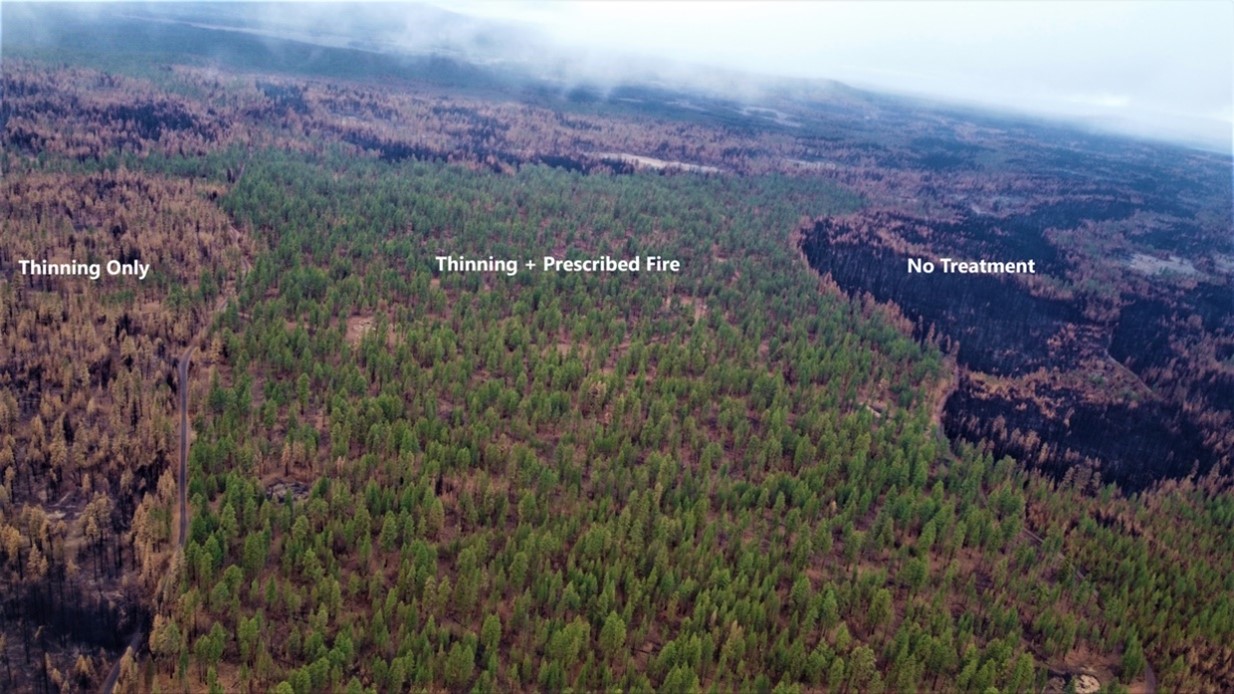

Bootleg Fire, Fremont-Winema National Forest. Where the wildfire met an area treated with prescribed burning and vegetation thinning, fire intensity lessened. Credit: Steve Rondeau, Natural Resources Director of the Klamath Tribes.

Bootleg Fire, Fremont-Winema National Forest. Where the wildfire met an area treated with prescribed burning and vegetation thinning, fire intensity lessened. Credit: Steve Rondeau, Natural Resources Director of the Klamath Tribes.

What are the challenges?

Despite its benefits, prescribed fire does come with some challenges:

- Impact to air quality

- Danger to firefighters

- Risk of escaping burn prescription and transitioning to wildfire

- Can be costly and time-intensive

- May need to be implemented repeatedly to see ecological benefits

- Spring and fall burning may not serve the same ecological benefits as summer burning

- Can aid expansion of invasive species like cheatgrass

- May work poorly in forests with infrequent, stand-replacing wildfires

Fire is complex, and as such prescribed fire as a management tool can be complex to implement. The success of a prescribed burn depends largely on the management goals associated with it, and the habitat in which the burn occurs. Success has been measured in dry ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests, but high-elevation subalpine fir and spruce forests, and wet forest types historically accustomed to fewer wildfires may not see as many ecological or commercial benefits from prescribed burning.

Prescribed fire is not necessarily the cure to the larger and more intense wildfires plaguing the Northwest, although it may be one in a suite of tools used to address the problem. Prescribed fire will not slow every fire, depending on weather and topography. But evidence shows that in many cases, prescribed fire can be an effective fire management tool if used appropriately.

Additional information on prescribed fire in the Northwest:

- Prescribed fire training exchanges (TREX)

- Northwest Fire Science Consortium

- Oregon State University Prescribed Fire Basics provides information about planning a burn, managing a burn, managing smoke, and much more.