Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

How do climate and wildfire relate?

Idaho, Oregon, and Washington are comprised of forests, shrublands, and grasslands that have cultural, economic, ecological, and social value. Although wildfires occur naturally and contribute to the long-term health of these ecosystems, changing wildfire patterns may put people at risk and have some negative effects on ecosystems. Wildfires in the Northwest have been immense in recent years. Large and severe fires are associated with warm and dry conditions, which are likely to intensify with climate change.

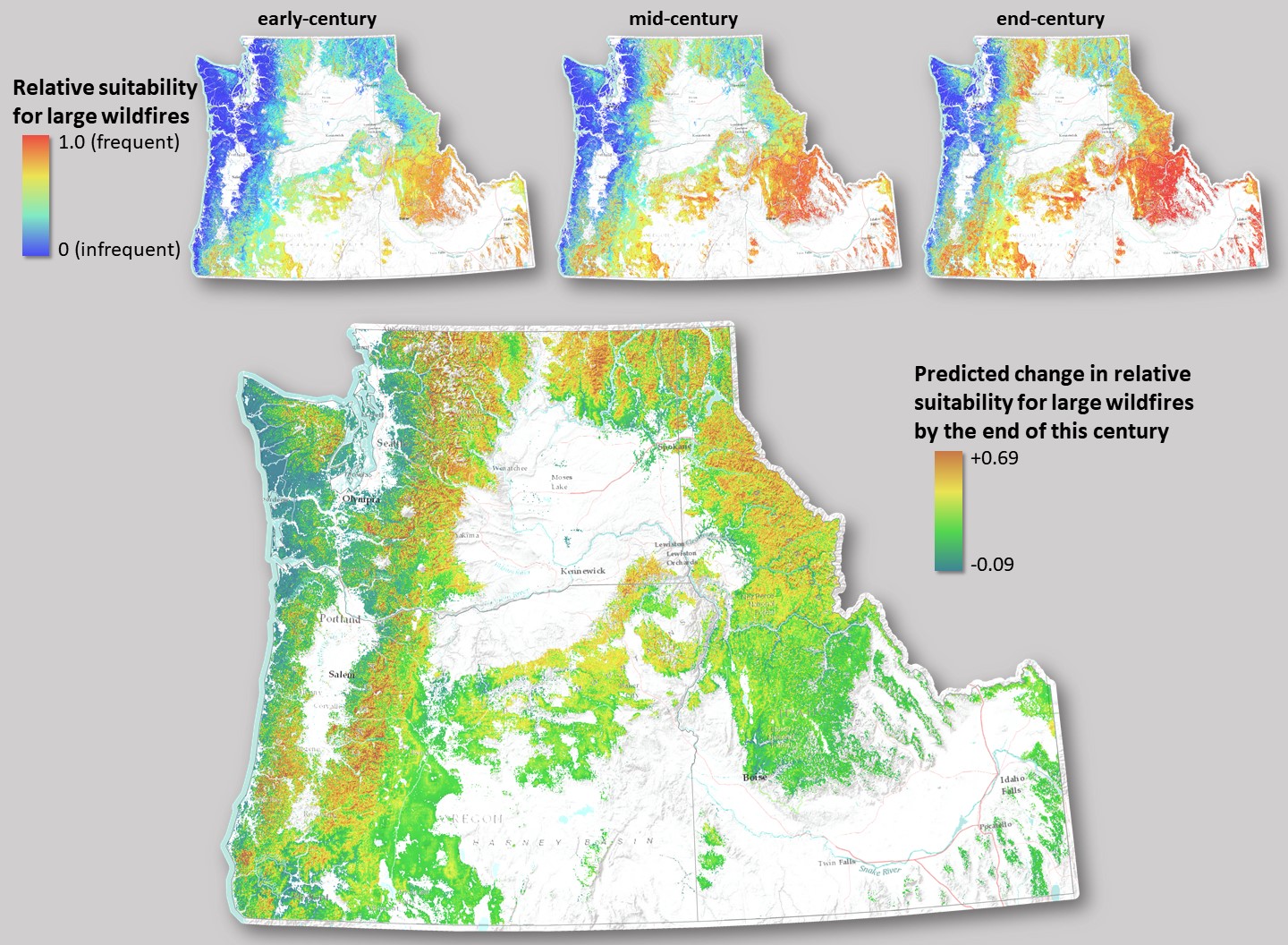

Climate and wildfire have been strongly related in the past, and changes in climate will affect future fire frequency and severity. Climate change could result in longer wildfire seasons, increased wildfire frequency, size, and total area burned, and possibly increased wildfire severity.

Several climate-related factors contribute to these changes in wildfire patterns in the Northwest:

- Increased temperature and drought

- Warmer springs

- Hotter and drier summers

- Drier soils and vegetation

- Earlier spring melting and reduced snowpack

- Decreased summer water availability

With higher temperatures causing soils and vegetation to dry, fires can start and spread more easily. Trends of longer wildfire seasons and larger wildfire size are predicted to continue as longer and more severe droughts occur.

Can we attribute recent wildfire events to climate change?

Single fires cannot be attributed to climate change unless a thorough, scientific attribution analysis of fire conditions is conducted. However, overall trends can be attributed to climate change (over 20- to 30-year time periods). Many recent trends in wildfire are consistent with climate change projections and what is expected in the future.

In Oregon, the 2020 wildfire season in moist forests on the west side of the Cascades caused extensive damage in some communities. Wildfires burned nearly as much forest in 2 weeks as had burned in the previous 50 years in the area. Several of these fires were also larger and more severe than fires documented in recent decades. Although the 2020 wildfire season registered as extreme in comparison to recent historical wildfire records in the region, paleo-ecological records show that fires of this size and magnitude (and some even larger) have occurred within the last several centuries. These fires shared similar weather conditions such as strong east winds and very dry conditions, occurring at the same time of year (August-September) and burning in some of the same locations.

The 2020 wildfire season west of the Cascades was significant but not unprecedented. Although it is tempting to infer that such a wildfire season was caused by climate change, a scientific attribution analysis is needed to determine the causal role of climate change in wildfires. Climate change may indeed play a role in the frequency, size, or severity of wildfires, but other factors may also influence wildfire in the Northwest, especially the unusual east winds that spread the recent fires. There is much to learn about the potential role of climate change on westside fires.

How will changing wildfire patterns affect Northwest forests?

More frequent and severe fires can slow the regrowth of vegetation and alter the species composition of Northwest forest ecosystems. High-severity fire creates opportunities for establishment of invasive species, such as cheatgrass, and can limit tree regeneration. In Northwest forests, a warming climate coupled with more frequent wildfires will lead to a shift away from shade-tolerant, thin-barked, or fire-intolerant species such as western hemlock, subalpine fir, and Engelmann spruce. Species that are fire-tolerant, thick-barked, and have high seed-dispersal rates, like Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine, are likely to fare well. However, with warmer and drier conditions and more frequent disturbance, there are some locations that will likely shift from forest to shrubland or grassland.

Short interval reburns (fires in areas burned within the last 15-20 years) are also likely to occur with increasing frequency. Frequent reburns can shift species composition toward species that are adapted to frequent fire. Some tree species will have a difficult time regenerating if intervals between fires are short, and shrubs and grasses may dominate for extended periods.

The increasing frequency of wildfire, particularly high-severity wildfires, will usher in more young forests as older, late-successional forests burn. This shift has major implications for species that depend on late-successional forests, such as the Northern spotted owl. However, some species, like deer and elk, could prosper in younger forests.

Contributing factors

There are other factors related to climate change that influence wildfire frequency and severity. Land use, lightning, invasive species, and management practices such as fire suppression all influence fire patterns in the Northwest.

-

Human-ignited fires already account for 70-90 percent of wildfires, depending on the state and year. With increasingly hot and dry conditions, typical outdoor activities could spark more wildfires.

-

Invasive grasses are also increasing wildfire frequency and size. Cheatgrass and other fire-tolerant invasive annual grasses are spreading into landscapes that did not have a continuous bed of fine fuels before, resulting in higher likelihood, frequency, and size of wildfires.

-

A 100 year-long, nationwide policy of fire suppression has also increased the likelihood of large and intense fires in the Northwest because of increased forest density and fuel levels.

Discerning changes in wildfire patterns requires an understanding of many complex socio-environmental elements.

What can we do about wildfires and climate change?

There are several adaptation strategies that can increase forest resilience and decrease wildfire intensity. Forest thinning and prescribed fire can reduce fire intensity and severity and increase forest resilience to fire, insects, and drought. In wetter, high-elevation, and coastal forests, managers can implement fuel breaks around valued resources. When post-fire planting of vegetation is possible, managers can choose species that are tolerant of drought and resistant to wildfire.

Curious how climate change could affect wildfire in Alaska? Check out the Hub webpage Climate Change and Wildfire in Alaska.

Fact Sheet

Northwest Fire Science Consortium – An organization that works to bridge the gap in Northwest fire science delivery, outreach, and application.

Great Basin Fire Science Exchange Network – An organization that works to bridge the gap in fire science delivery, outreach, and application across the Great Basin.

Northern Rockies Fire Science Network – A resource for managers and scientists involved in fire and fuels management in the Rocky Mountains of Idaho, Montana, Washington, and Wyoming. They strengthen collaborations, synthesize science, and enhance science application to critical fire and fuels management issues.

Braiding Indigenous and Western Knowledge for Climate-Adapted Forests – A report from the USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station, Oregon State University, and University of Washington that includes guidance on how to blend indigenous and western knowledge to adapt western forests to changing wildfire patterns associated with climate change.

Firewise promotes fire safety in the wildland urban interface (WUI) and helps communities to implement fire safe practices across the United States.

-

Climate Change and Wildfire in Northwest Rangelands

The risk of large, frequent, and severe rangeland wildfires is increasing as warming temperatures and invasive annual grasses alter rangeland ecosystems.

-

Climate Change and Wildfire in Alaska

In Alaska, the risk of large, frequent, and severe wildfires is increasing as rapidly warming temperatures and longer growing seasons alter forest and tundra…

-

Prescribed Fire in the Northwest

Advantages and disadvantages of prescribed fire in the northwest and the process of conducting a prescribed fire.