Reading time: 9 minutes

Here at the Northwest Climate Hub, we recognize that the effects of climate change may have caused damage or distress to many of our readers. Reading about climate change may be triggering, so if you are suffering from mental health impacts because of climate change, please reach out to the Disaster Distress Helpline.

Key Points

- Drought affects agriculture differently depending on location, severity, and length.

- While lack of precipitation can trigger droughts, in some places, rising temperatures have become a bigger factor in drought severity in recent decades.

- Reduced irrigation water availability and lower soil moisture associated with drought can affect agricultural production.

- Drought can cause severe economic losses, as it did in 2015, when a drought in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington led to $1 billion in losses.

- Drought can heighten existing tensions over water use as agriculture, communities, fisheries, and hydropower compete for the same water resources.

- Despite the many challenges that accompany agricultural drought, there are adaptation actions that can help farmers build resilience to climate change.

Idaho, Oregon, and Washington host orchards that brim with apples, vineyards that stretch across rolling hillsides, golden dryland wheat fields, and millions of acres of irrigated row crops. With over 40 million acres of farmland, the Northwest is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the country and a top producer of many important crops. However, as climate change intensifies, agricultural droughts could become longer and more severe. Drought can have significant effects on agricultural productivity, and can threaten the agricultural economy, farmworker health, and food security in the Northwest.

What is agricultural drought and how does climate change affect it?

Agricultural drought occurs when crops are affected by meteorological drought (drier-than-average conditions over a prolonged period) or hydrologic drought (low water levels). Because the Northwest is a diverse region with a range of precipitation and temperature patterns, the effects of drought vary by location. For instance, in the arid and semi-arid regions of the Northwest (e.g., southern Idaho, eastern Washington and Oregon), the impacts of drought on the agricultural community have been more severe than in the cooler, wetter parts of these states. However, as the climate changes, the impact of drought is likely to intensify and spread to more agricultural regions throughout the Northwest.

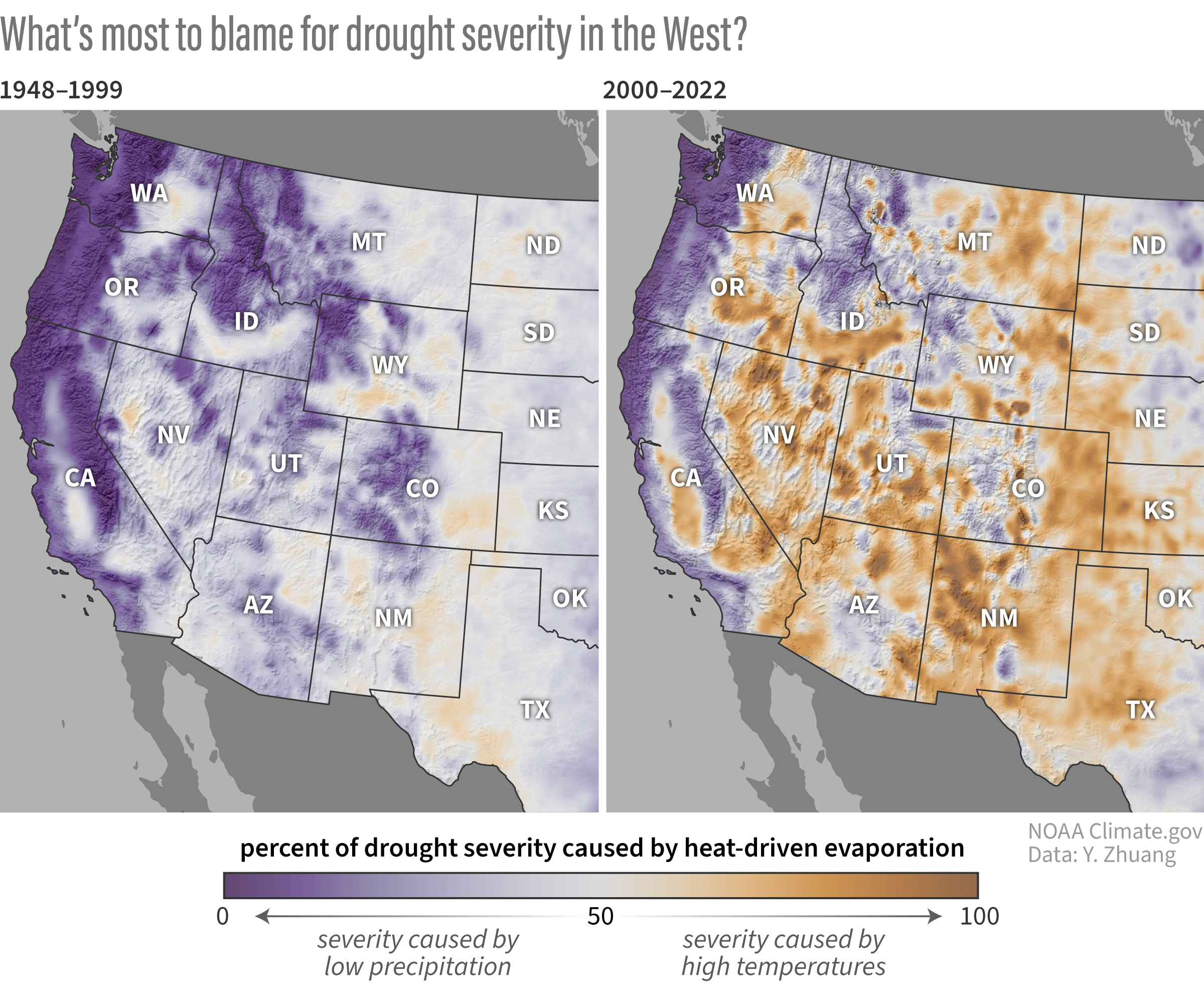

Regional temperatures have already risen nearly 2°F since 1900. By the end of the 21st century, climate change is projected to raise regional temperatures by 4.7–10.0°F. Since 2000, high temperatures have actually played a larger role in drought severity than lack of precipitation. For example, evaporation associated with higher temperatures accounted for 61% of the 2020 to 2022 drought's severity, whereas reduced precipitation only accounted for 39%. This is because hotter temperatures cause increased evapotranspiration, or the loss of water from the soil both by evaporation from the soil surface and by transpiration from the leaves of the plants growing on it. With higher temperatures, plants have to acquire and transpire more water than they do in cool conditions (think of this like humans having to drink more water when it is hot). This is known as increased evaporative demand. A higher evaporative demand means less moisture can be stored in the soil and in plants themselves. This can stress plants, and even cause plant death.

Alongside high temperatures, drier-than-average conditions and reduced snowpack can also contribute to agricultural drought. Though climate change may lead to a slight increase in annual precipitation across the region, summer precipitation is expected to decrease. Furthermore, more precipitation will fall as rain, rather than snow, reducing snowpack. Beyond increased evaporative demand, rising temperatures could cause the snow that does fall to melt earlier in the year. These changes will affect soil moisture and irrigation water availability throughout the growing season.

How are crops affected by drought in the Northwest?

Drought poses significant challenges to agricultural production. Limited water availability can cause plant stress, leading to reduced crop yields and quality. Annual crops (e.g., potatoes, hay, and onions) can experience reduced yields and quality associated with drought. But perennial crops (e.g., apples, cherries, pears, and apricots) can take years to recover from drought, and may not ever fully recover. The threat of drought can also deter farmers from planting certain annual crops, resulting in lost potential harvests. The likelihood of simultaneous extreme heat and drought events is also increasing with climate change. Crops are more vulnerable to heat stress during drought, which can further reduce yields. In addition, drought can contribute to insect outbreaks, wildfires, and soil erosion, all of which can negatively affect agricultural productivity.

Because most Northwest crops are irrigated, reduced irrigation water availability can affect agricultural productivity. In most places in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, a reliable supply of irrigation water depends on the gradual melting of mountain snowpack throughout summer. Yet, climate change is projected to reduce snowpack and cause earlier snowmelt. These changes could reduce groundwater recharge, streamflow, and reservoir levels, limiting irrigation water availability for crops during late stages of the growing season. Simultaneously, warmer, drier conditions will increase crop water demand, further straining water resources.

Water quality can also be affected by drought. When water levels in streams, rivers, or reservoirs decrease, the concentration of nutrients can increase, and water temperatures can rise. These changes can lead to higher salinity levels, increased algal blooms, and more pollutants in waterways. Poor irrigation water quality can negatively affect plant growth, reducing crop quality and yields.

The Northwest also produces a variety of non-irrigated crops, including dryland wheat. These crops rely on residual moisture stored in the soil throughout the growing season. Though many dryland farms employ adaptation practices that increase their resilience to drought, dryland crops can still be affected by reduced soil moisture retention and increased evaporative demand. Drought and high temperatures can deplete soil moisture, potentially leading to lower yields and reduced quality.

Drought has many implications for agriculture in the region. The table below includes a few specific examples of agricultural drought impacts experienced in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington since 2005.

Drought Category | Examples of historically observed impacts of drought on agriculture |

D0 – abnormally dry | Dryland crops stressed; fields left fallow (unplanted); alternate crops planted in anticipation of drought; water allotments reduced |

D1 – moderate drought | Some irrigators switch from surface to groundwater irrigation; junior water rights holders receive less water; cranberry harvest delayed |

D2 – severe drought | Small grain crops fail; irrigators lose access to water; groundwater pumping stopped; farmers irrigate fewer acres; conflicts with other sectors that require water occur |

D3 – extreme drought | Wheat yields significantly reduced; reservoirs extremely low or empty; soil erosion increases; domestic wells run dry; apples, cherries, pears, and raspberries smaller than average; lower yield of seed potatoes; pumpkin crop failures |

|

D4 – exceptional drought | Pear production reduced by 25-100%; wheat yield reduced by 50%; blueberry yield, quality, and size reduced; severe grasshopper outbreaks; crop losses common; empty streams, canals, and reservoirs |

How can farmers and consumers be affected by drought?

Farmers in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington are no strangers to drought. They have successfully adapted to drought in the past, including events in the 1930s, 1970s, early 2000s, 2015, and from 2020 to 2022. However, for farmers already contending with more extreme heat, flooding, and economic challenges, drought can introduce one obstacle too many. Conflicts over access to water can further exacerbate stress associated with drought. For consumers, drought can affect food pricing, accessibility, and quality. Climate change is likely to intensify these challenges.

Economics and human health

The agriculture industry creates nearly 300,000 jobs and generated $18.5 billion in sales in 2022, making up more than 13% of each state’s economic activity. As such, drought can have a severe economic impact on farmers, farmworkers, and agricultural communities. When crop yield or quality are reduced, farmers have less to sell or receive lower prices, resulting in decreased revenue. In 2015, for example, drought caused agricultural losses in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington to reach nearly $1 billion, including extensive losses to raspberries, blueberries, and the dairy industry. The threat of drought can also cause farmers to delay plantings or leave fields fallow (unplanted), reducing the number of crops that can be harvested and sold.

Reduced yields and quality can strain farmers' finances and reduce the demand for farm labor, which can jeopardize farmworker income. Industries dependent on agriculture, such as food processors and fertilizer companies, can also suffer secondhand from the effects of drought. In addition, food and water shortages can cause costs to rise for farmers and consumers alike.

As climate change increases the duration and severity of agricultural drought in the Northwest, farmers, farmworkers, and communities could face increasing health risks. Northwest farmers are deeply concerned about the effects of drought on their operations. In Oregon, 60% of farmers surveyed identified drought as one of their top weather-related concerns. For farmers, people who already face high rates of depression, drought has been linked to mental distress, reduced life satisfaction, and increased suicidality.

Despite the economic challenges associated with drought in the Northwest, drought can be even more devastating in areas of the globe with less water. As drought affects more of the world, the demand for agricultural products from regions that are typically water rich, such as the western parts of Oregon and Washington, might lead to increased profitability for some Northwest famers. In an example, drought in the Midwest is often associated with higher prices and more profit for farms in Idaho. However, to profit from increased drought worldwide, farmers in the Northwest will need to adapt to local changes in climate.

Conflicts over water use

Drought can heighten existing tensions over water use as agriculture, communities, fisheries, and hydropower compete for the same water resources. In the Klamath Basin of southern Oregon, for example, the increasing demands of agriculture, fisheries, and downstream communities have often exceeded the available water supply, creating a complex and contentious situation. However, there are examples of farmers in the region working with anglers and others to improve wildlife habitat, conserve water, and enhance crop yields.

Tensions between producers can also increase during drought. Idaho, Oregon, and Washington use prior appropriation doctrine, which grants rights to surface water and groundwater based on seniority. This means that the person who owns the oldest rights to water from a particular source is the last to be shut off during low water conditions. They can use their full allocation of water without regard for the needs of junior users. During periods of drought, this can leave irrigators with junior water rights particularly vulnerable, as they may receive little or no water.

Idaho, Oregon, and Washington allow for leasing of water rights and temporary exchange of water rights through water banks, which can reduce the vulnerability of junior rights holders if they have the resources to purchase additional water. However, as climate change alters water availability, tensions over water rights are likely to persist.

What can farmers do to prepare for more drought in the future?

Despite the many challenges that accompany agricultural drought, there are adaptation actions that can help farmers build resilience to climate change. As drought becomes more frequent and severe, farmers in some areas may shift to drought-resistant crop or varieties. Researchers throughout the Northwest are already developing drought-resistant varieties of dominant crops, such as wheat. Investing in soil health can also help farmers reduce the impacts of drought. Practices such as no-till farming, cover crops, and agroforestry can improve soil moisture retention and reduce water loss. Climate-informed irrigation systems, such as micro-irrigation and variable-rate irrigation technology, can enhance water application efficiency while reducing energy and water use. For junior water-rights holders, temporary water leasing during drought years can reduce impacts of drought, when available.

When drought affects farmland or farm revenue, crop insurance can lessen the financial impacts. USDA has many other programs that can help insured and uninsured farmers who have experienced farmland damage, crop losses, and more. With adaptation, there is hope that farmers can build resilience to drought and continue to support a thriving agricultural economy and regional food security in the Northwest.

The Farmers.gov Drought Page includes information about many types of drought recovery, protection, and loss reporting.

2015 Drought and Agriculture is a study by the Washington State Department of Agriculture that explores the impacts of the 2015 drought on agriculture in Washington.

The Annual Assessment of Water Year Impacts in the Pacific Northwest reviews the significant weather events and climate conditions of the water year, captures the water year impacts, and provides a forecast for the upcoming water year.

Idaho Risk Assessment Drought Chapter includes a wide range of information about historical, current, and future drought conditions in the state.

Columbia River Basin Long-Term Water Supply and Demand Forecast is a tool that allows water managers in the Columbia River Basin to plan for future water needs or infrastructure investments at multiple scales.

Beating the Heat is a statewide assessment of drought and heat mitigation practices (and needs) for Oregon farmers and ranchers.