This year is different for Cecarelli Farms.

In late January 2018, Nelson Cecarelli passed away after a battle with cancer. His legacy of agricultural stewardship and passion for farming continue through his business partner and friend, Will DellaCamera. Over the past 20 years, Nelson and Will managed Cecarelli Farms together. Nelson was often the one riding the tractors and taking care of all the planting details. Will was the mastermind behind engineering new machinery add-ons to make a more efficient and precise production system.

This past summer, a field of sunflowers were planted in memory of Nelson. These towering, sun-worshipping blooms will do more than just look beautiful. Proceeds from these sunflowers will go to a fund in Nelson's honor and used by students in financial need who display keen interest in going to school for agriculture.

New Responsibilities and Decisions

As one might assume, Will has been busier than ever. In picking up the responsibilities Nelson once had, Will now adapts in order to keep the farm operating smoothly. This includes taking on all the planting decisions (i.e. what to plant, how much to plant, where to plant, and when to plant it), overseeing employees and sales, and monitoring and managing for pests while also updating the farm’s irrigation system. In addition to all this, the farm’s Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program has almost doubled in memberships since last year, now 100 members strong.

“So, the tomatoes I planted just as many, if not more than last year. But tomatoes bring big money. The corn is about half of last year. The peppers are half of last year …Why did I choose to grow only half that stuff? I chose to do it because… years past… there’s a hard time to sell a lot of that stuff, and that’s between really when sweet corn starts to pick heavy and the beginning of July. So, you’re looking at the first… week of July, especially around the Fourth of July because the wholesalers and stores are closed this day, open that day, shut down this day, and it was hard to move it.”

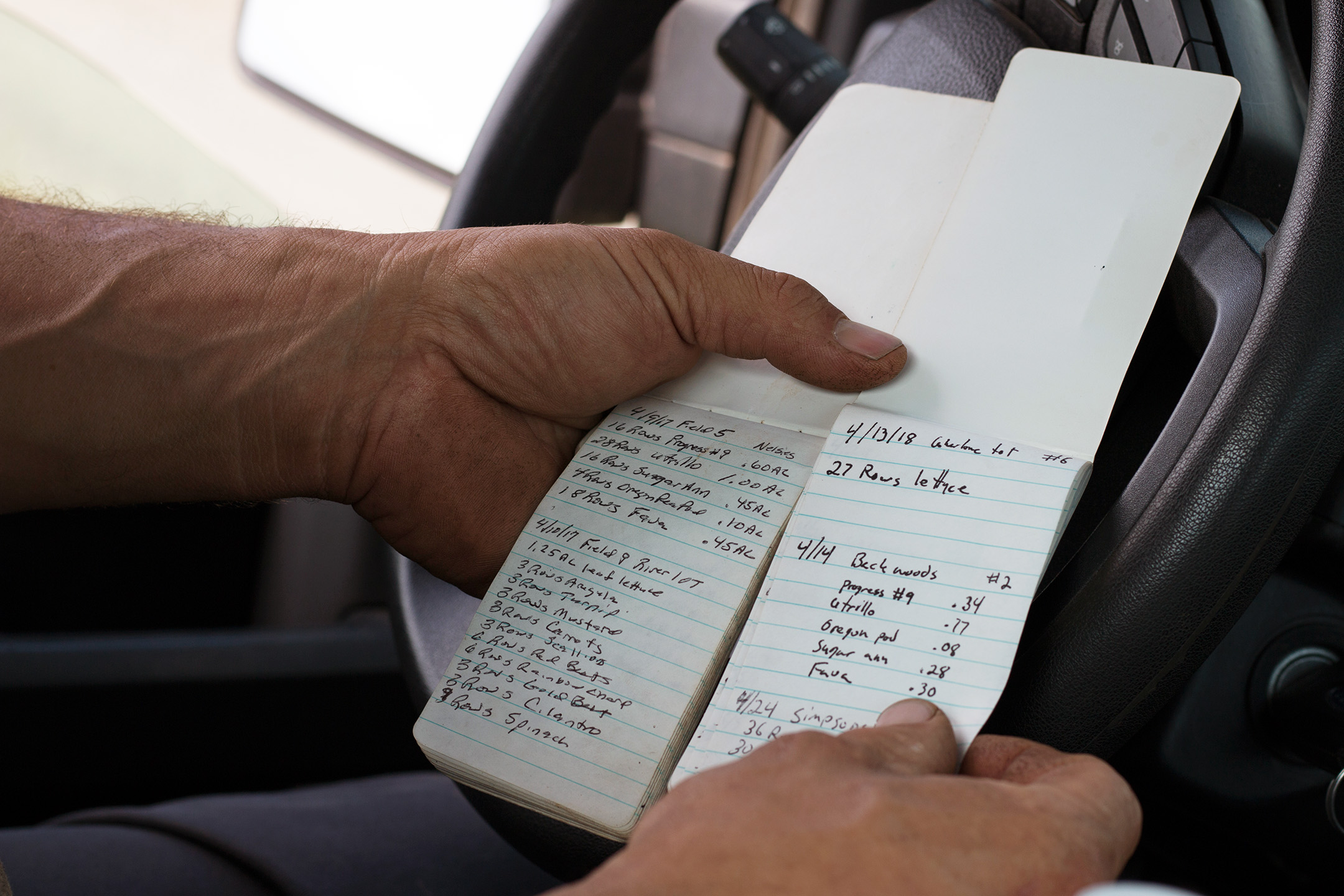

PHOTO: William DellaCamera compares annual planting notes. The notebook on the left was logged by Nelson Cecarelli in 2017.

By planting more of some crops (i.e. tomatoes) and less of others (i.e. corn, squash, peppers), Cecarelli Farms is fine-tuning its planting schedule based on past sales trends. This way they try to anticipate and be more receptive to consumer and wholesaler demand. This can mean less energy, resources, and labor inputs needed by the farm. Scaling back planting this season also provides Will with some leeway, albeit not much, as he shifts into the responsibilities of full farm management.

“It’s a lot of stuff to pick, so I chose to cut that down a little bit. It was the only way it was going to work. There were some cuts I made here and there just because I knew what it’s done to us in the past.”

PHOTO: William DellaCamera shows off a bunch of freshly harvested onions on July 13th, 2018.

When Will does have a moment to pause, he confides that it’s been hard not having Nelson around anymore, especially for simple things like being able to bounce new ideas around or figure out a problem together. However, Nelson did make sure one potential setback was ironed out before his passing. In his early career as an insurance agent, Nelson had seen the value of farm succession planning. Because of this, he made sure Cecarelli Farms had a transition plan in place. Nelson had also encouraged Will to take classes on the topic a few years ago. And now, as Will navigates the farm’s future, those classes have proved helpful.

According to the 2012 Census of Agriculture (USDA NASS), the national average age of principle farm operators was 58 years. And since nobody ever gets younger, proper foresight for a farm’s longevity and future is important. Farmers adapting to current and anticipated changes in climate must consider the farmers of tomorrow. In other words, succession planning and adapting to climate change should go hand-in-hand if we are all to have an enduring regional food system.

Dealing with Extremes in the Growing Season

This past spring and summer, many in the region have experienced weather extremes from heavy downpours and flooding to record breaking heatwaves. Cecarelli Farms was no exception. In mid-May, after starting the planting season a little later than usual due to cool spring temperatures, a tornado (yes, a tornado) with heavy rains caused considerable damage in the community. Luckily, aside from a few downed trees in a managed woodlot and the need to run a generator for a couple days, Cecarelli Farms’ only production setback from the tornado was a shift in planting locations. The tornado hit a field intended for corn just after Will had deep zone tilled the soil. All of the heavy rain made it too wet for planting, and the corn had to be planted into a different field.

PHOTO: William DellaCamera drives by the corn fields on July 13th, 2018.

"This planting was planted right after we had our tornado incident. That’s why there’s such a jump there. [On] May 18th I planted that corn you see with the tassels on it, right there. There’s a planting over there that was planted on May 30th… so that was 12 days apart. That tornado came, and it dropped like four inches of rain. And we had [deep] zone tilled it to plant over there, and it was so muddy. I needed to go somewhere to plant. So, we moved over here, and I planted this because it wasn’t zoned tilled. One downfall of zone tillage… if it’s zone tilled, and it gets poured on, all bets are off. It gets so muddy… you can’t plant.

Deep zone tillage (DZT) is a management practice used to protect soils and reduce run-off from heavy rain events. A DZT machine works by tilling a very narrow, but deep strip of land that is just wide enough for crops. These ‘narrow but deep’ characteristics cause minimal soil disturbance and are what allow for greater root structure depth and greater rain absorption abilities. Cecarelli Farms first adopted this tillage method after a series of heavy rainstorms in 2006 eroded and washed away much of their freshly turned topsoil. However, there is a window of vulnerability associated with this practice. As Will noted, if very heavy rain occurs soon after a field has been deep zone tilled (but before crops are planted), the rain will penetrate the earth so deeply and quickly that the field will then become too wet to work.

PHOTO: A sloping corn field at Cecarelli Farms with different plantings of corn on July 13th, 2018.

In addition to heavy rain events, hot, humid weather has also hit much of the Northeast this summer. In fact, according to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, seven states in the Northeast had July temperatures that ranked within their top ten hottest on record. Although the heatwave in early July might have felt brutal to many, it helped immensely with crop growth at Cecarelli Farms. Irrigation was vital to ensure crops were sustained during the heatwave (as heat stress can impact crop yields).

In addition to heavy rain events, hot, humid weather has also hit much of the Northeast this summer. In fact, according to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, seven states in the Northeast had July temperatures that ranked within their top ten hottest on record. Although the heatwave in early July might have felt brutal to many, it helped immensely with crop growth at Cecarelli Farms. Irrigation was vital to ensure crops were sustained during the heatwave (as heat stress can impact crop yields).

The Northeast will continue to see increasing variability when it comes to periods of ‘too wet’ and ‘too dry.’ Agricultural systems are likely to become more stressed from such weather extremes, plus the continued trend for warmer temperatures in the region also has implications for higher occurrences of heat related illnesses. Understanding the causes, symptoms, and treatments can certainly help farm operations avoid these heat-related health problems.

Building an Irrigation System

Heat and drought concern farmers in all corners of the country. Although such issues are not new, they are becoming more frequent and extensive. So, does irrigation make sense as a farm strategy given the trend in the Northeast is actually for more rainfall? As it turns out, according to this economic case study, it may. The ‘more rainfall’ trend that is occurring is often happening in heavy downpours between periods of hot and dry weather. And these periods of hot and dry weather within a now lengthier growing season are causing water scarcity to increase.

Cecarelli Farms is not the first, and they also won’t be the last farm to rethink their water use needs and irrigation system under the changing climate. Currently, the farm relies on retention ponds for water, and diesel pumps to deliver it around the farm to all the different fields. Since water access is currently limited, the efficient use of water is of the utmost importance for success. Will hints at future plans to drill a well outfitted with an electric pump, but his current focus is on transforming the farm’s existing irrigation system into a subsurface drip irrigation system.

PHOTO: Installation of subsurface drip irrigation lines at Cecarelli Farms. | Photo by William DellaCamera

Subsurface drip irrigation (SDI) is a low pressure, high efficiency watering system by which drip tube lines are buried below ground. Because the irrigation lines in an SDI system are buried, there are quite a few benefits. By its very nature of being below ground, there is no surface water evaporation taking place. And so, water and nutrients can be more targeted to the actual root zones of thirsty, growing crops. More targeted water and nutrients to crop root zones (~10”-12” down) means increased crop yields. Reduced weed populations are also an observed outcome since most weed seeds tend to germinate closer to soil surface. Altogether, a properly installed and maintained SDI system can greatly improve crop yields, conserve water, and reduce labor and herbicide costs due lower weed populations.

Subsurface drip irrigation (SDI) is a low pressure, high efficiency watering system by which drip tube lines are buried below ground. Because the irrigation lines in an SDI system are buried, there are quite a few benefits. By its very nature of being below ground, there is no surface water evaporation taking place. And so, water and nutrients can be more targeted to the actual root zones of thirsty, growing crops. More targeted water and nutrients to crop root zones (~10”-12” down) means increased crop yields. Reduced weed populations are also an observed outcome since most weed seeds tend to germinate closer to soil surface. Altogether, a properly installed and maintained SDI system can greatly improve crop yields, conserve water, and reduce labor and herbicide costs due lower weed populations.

There is never a magic bullet when it comes to farming, and SDI also has its drawbacks. Installation of such a system can often have high upfront investment costs in terms of both money and time. Variables such as soil characteristics, crops, water source(s), materials used, and degree of system automation are all likely to vary from farm to farm… and so too will results.

PHOTO: “That’s beautiful, and it doesn’t go anywhere,” comments William DellaCamera as he digs down to show the soil moisture difference between soil from the surface and soil that’s around a buried irrigation line on July 13th, 2018.

“point-two-five gallons a minute for every hundred feet. So, each one of these is 600 feet long. So, it’s putting down a gallon and a half a minute [per tube]. So, the whole block times eight is fourteen gallons a minute, right? So, that’s not bad. My little irrigation pump I have with a sprinkler on it… and it’s only a little gun… it’s a 200-foot circle… and it puts out 210 gallons a minute. That’s a lot of water. It don’t take but a few minutes to start dropping the pond.”

Before the installation of an SDI system, the farm used a combination of drip irrigation lines (under the plastic mulch) and sprinkler guns. To start the SDI project, Will first built a special attachment used to insert the irrigation tubing underground. With this on board, Will was then able to rig a tractor that buries an irrigation line in tandem with creating a small raised bed that can then be planted without plastic mulch. This installation method is especially useful for row crop vegetables that don’t use plastic mulch, like corn. Although plastic mulch is useful for some crops because it heats the ground up faster and keeps weeds at bay, Will’s overall goal is to get away from plastics. Will’s decision to use less plastic is an economic one, but there are trade-offs to contend with such as potentially more weeds and herbicide costs. Using less plastic mulch means less material costs and less labor time at the end of the season for Cecarelli Farms. Regardless of the use of plastic mulch, SDI tubing installed under all crop fields will allow the farm to water and fertilize all its plants more efficiently. So far, most fields have already been outfitted with the new system. Only the bean and cabbage fields still remain to be addressed. By the end of the growing season, Will plans to finish his installation of SDI lines across all crop fields.

“See that yellow thing with the spike? That’s what puts the spike in the ground [for the irrigation tubing] …the tube goes on top of that yellow thing… and then it goes down underneath. When it lays the plastic [mulch], it puts the fertilizer down and makes the raised bed. And then the tube goes down through that pipe and it gets buried in the soil. And then see the tube underneath the plastic? That tube goes to the other end …this tube is buried under the tomatoes all the way to the other end.”

PHOTO: William DellaCamera explains how subsurface drip irrigation lines are set down on July 13th, 2018.

Anticipating Labor Needs with Extended Seasons

Many longtime farmers feel that the seasons have shifted, and the latest climate models indicate that these changes are likely to continue. Earlier springs, extended growing seasons, and lengthier falls offer opportunity for greater agricultural yields in the Northeast, especially for those in New England where seasons are already short. Heat tolerant crops and woody perennials will likely thrive under these conditions, while many cool weather crops will most likely face a shortened growing season. However, the agricultural benefits of an extended growing season may not easily align with a farm’s labor force (if on a contract basis). Farms with hired labor may soon need to re-evaluate their labor costs and needs against the profit potential from continued harvests with lengthier, warmer falls becoming the new normal.

“For some reasons, I’d want everything we grow on plastic [mulch] because of the weed control and the ease of watering and all this other stuff, but then on the other hand, they have to be here for us to pick all that plastic up. That’s a lot of plastic. So, now you might go in and cut strings and take stakes out just because they’re going to leave on you, and you better have that picked up.”

PHOTO: Rows of tomatoes planted in raised beds and black plastic mulch at Cecarelli Farms on July 13th, 2018.

With this is mind, Cecarelli Farms decided to also lay out some plots of field tomatoes and peppers without the use of plastic mulch. If the growing season extends later than normal into late October like it did last year, they will be able to benefit from continued harvests while also minimizing their labor needs post-harvest for these specific fields.

With this is mind, Cecarelli Farms decided to also lay out some plots of field tomatoes and peppers without the use of plastic mulch. If the growing season extends later than normal into late October like it did last year, they will be able to benefit from continued harvests while also minimizing their labor needs post-harvest for these specific fields.

“But, now I have a block of tomatoes and a block of peppers that I only need one or two guys to clean that up… So, yeah, it might be a pretty substantial block of tomatoes, but, yes I can extend that season that much longer because I need less labor to clean up.”

Unfortunately, there are additional problems arising from the shift in seasons that will impact agriculture. For instance, the life cycles and migration patterns of many species -such as when flowers bloom or when pollinators emerge- are being disrupted. And numerous weed, disease and pest pressures are intensifying and moving northward with the help of longer growing seasons and milder winters.

However, as illustrated by Cecarelli Farms, there are many actions farmers take to lessen the impacts – or even take advantage of - these climate trends. As already highlighted through conversations with Will, some actions include the farm’s use of deep zone tillage to combat soil erosion from heavy rains, installation of a SDI system to more efficiently target water to crop roots (and reduce weed germination, labor, and other resource inputs), adjustment of planting decisions in anticipation of a lengthier harvest window for some crops due to later frosts dates (but with a reduced labor force), decisions based on data from an on-farm weather station, and being responsive to both weather events and market demands in order to conserve both time and resources.

PHOTO: View from behind the farm house on Cecarelli Farms on July 13th, 2018.

Photo essay by Karrah Kwasnik, Digital Content Manager, USDA Northeast Climate Hub in conversation with William DellaCamera, Farm Manager and Vegetable Farmer, Cecarelli Farms on July 13th, 2018

Initial Conversations with Cecarelli Farms

In late 2017, Farm managers, Nelson Cecarelli (1954-2018) and William DellaCamera, candidly speak about their diversified vegetable operation in Northford, Connecticut, and the changes that their farm has gone through to become both a more sustainable and efficient operation.

![[left to right] David Hollinger, William Dellacamera, and Nelson Cecarelli [left to right] David Hollinger, William Dellacamera, and Nelson Cecarelli](/sites/default/files/styles/wide_article_ratio/public/groupshot_0.jpg?itok=s6ju3h8h)